Dropbox for iOS

Dropbox is one of the most well known cloud storage services in the planet. It needs little to no introduction. In this post I look into what relevant digital forensic artifacts can be found for Dropbox in iOS.

|

|

This post will differ from previous ones in that I will not discuss how to locate the application data directories or how to extract them. For an example on how to go about doing so follow the steps (which are for the Discord app but work for any app)

here.

Short Summary

Dropbox SQLite databases contain information regarding files stored in the cloud even when the files themselves are not downloaded to the device. Two of my favorite findings are:

- The ability of matching app generated thumbnails on the device to the full metadata information from the original remotely stored files.

- Database tracking of how many times a file was viewed via the app even if the file wasn't downloaded or synced.

Additional data was contained within the app directories outside of SQLite databases. If the account in use is linked to a third party provider, like Google, a JSON file is generated with all your contacts and any Dropbox interaction that took place with the target user account. Some of the data in the JSON file are names, usernames, profile pics URLs, and timestamp of the latest Dropbox interaction like the sharing of a folder. In addition the Dropbox target user account information can be found in one of these JSON files.

Important Information

All the queries and analysis in this blog post is provided as a guide for the reader's own testing and validation.

Testing Platform

For analysis I am using the following device and equipment:

- iPhone SE - A1662

- iOS 11.2.1

- Jailbroken - Electra

- Forensic workstation with Windows 10 and SSH software.

- Magnet Forensics Axiom 2.71.12070 with custom queries made by the author.

Analysis of SQLite databases

The Dropbox app has the following file directory structure:

Most of the databases of interest are in the /Documents and /Documents/Users/

UserID directories where

UserID is the numeric representation of the user account. The contents of the /Documents directory are as seen in the next image.

|

| First database of interest. |

Spotlight.db

The first database of interest, as seen above, is spotlight.db. This database seems to be the partial aggregation of the data contained in two other databases within the /Documents/Users/

UserID directory. These will be discussed shortly. After running the query above for this database (

Spotlight - recent actions) we get the following:

Spotlight.db selection.

Salient items:

- Path: Path and filename of remotely stored file.

- Source: From where the activity information came from. I found no files named as such in the Dropbox app directories.

- Title: Filename.

- Last action time: Timestamp. For files that end in .remote in the source field these timestamps match when the app was opened. For files that end in .local in the source field these timestamps match when the user had interaction last with those files.

Based on the files names it seemed to me that this list is composed of the items one sees in the recents screen after login into the app. Older files that I did not scroll down to are not in the list. The content of Spotlight.db mirrors the content in two other databases called recent_actions_local.db and recent_actions_server.db. These databases are contained in the following location:

/Documents/Users/UserID/

Recent_actions_local.db

This database contains the same entries that end in .local within the spotlight.db source column. The only addition is the user id column. Here is how running the query above (

Recent actions local) looks like:

Salient items:

- Path: Path and filename of remotely stored file.

- Timestamp: Time user interacted with the file last. I clicked on the thumbnails of these items in the app to view them. One of them I made available offline. The times are the same ones as contained in spotlight.db.

- User ID: User identifier.

There might be more user actions that will flag a file as local recent actions. The databases do not specify what that action was or could be. So far I have only been able to flag the files by the actions stated previously.

Recent_actions_server.db

This database contains the same entries that end in .remote within the spotlight.db source column. The only addition is the action column. The timestamp is different from the spotlight.db time. Here is how running the query above (

Recent actions server) looks like:

Salient items:

- Path: Path and filename of Dropbox stored file. Not local.

- Action: Human readable message.

- Timestamp: The times in this column follow closely the time the image was taken (see next section for details.) By comparing the filenames with the timestamp column I concluded that the timestamp reflect when the image was added to Dropbox. I have my Dropbox set up to only upload images when connected to WiFi.

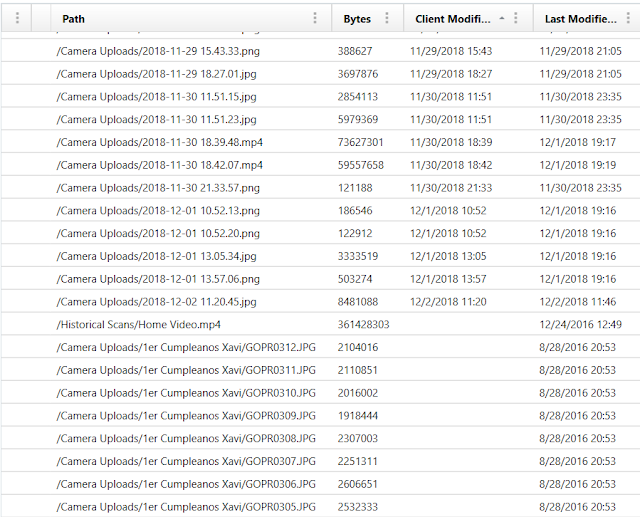

Camera uploads and naming convention

My testing showed the following regarding file naming convention and timestamps for the camera uploads directory:

- Images taken by the mobile device camera and uploaded automatically by the Dropbox app are named in Dropbox as the creation date of the image on the device.

Sample image and metadata on the device. Notice the original filename and creation timestamp.

Now notice the filename Dropbox gives it after it uploads it.

- If the user herself uploads files and images to the Camera Uploads folder, as opposed to the app itself, these will retain their original names.

- Files can come from different devices and land in the same Dropbox remote storage account. These databases do not tell us what device produced or uploaded the images originally.

Thumbnails

Be aware that by default the app will create thumbnails for the items on the list at the following location:

/Library/Caches/Uers/UserID/FileCache/Loaded/

The directory has a collection of folders named in a simple pattern of lowercase letter p followed by a number.

Inside these folders thumbnail files will be stored with the following filenames:

- 256x256_fit_one_bestfit

- 960x640_bestfit

If one of the images was downloaded to the device or placed as available offline the folder will contain an additional image named:

The following image shows the contents when all three are present for the p5 folder.

The obvious question becomes, how are these images matched to the items previewed, viewed, or downloaded by the user in the Spotlight database? The answer is that there is no link to the thumbnails in that database. The link is found in a different database called Dropbox.sqlite.

Dropbox.sqlite

The Dropbox.sqlite database has metadata on all cached files. Here is how running the query above (

All cached files metadata) looks like:

The column named Cached File ID has the number needed in order to match the thumbnail to the full size image stored within Dropbox. It is as simple as putting a p in front of the number and looking for it in the thumbnails directory.

Salient items:

- Cached File ID: Number that corresponds to the thumbnails folder. Just add a 'p' in front of the number.

- Path: Path and filename of Dropbox stored file. Not local.

- Cached File Size: In bytes.

- File size: Actual file size. Item not local.

- Times viewed: How many times the user click on that thumbnail to view a larger version of it.

- Last time viewed: Just what it means.

was generated that looks as so:

This is one of the most direct ways of demonstrating user activity tied to specific items.

Additional databases of interest in the /Documents/Users/UserID/ directory are metadata.db, offline.db, and starred_infos_local.db.

Metadata.db

This database is interesting because the contents mirror user activity when files are browsed through the Files menu in the app. It will record folders and file names. A query was generated (

Browsed files via the 'Files' menu option) to show these contents.

Salient items:

- Path: Path and filename of Dropbox stored file. Not local per testing conditions.

- Last Modified Date: Notice how the root folder and Dropbox generated directories (Camera Uploads, Public, etc...) do not have a Last Modified timestamp while user generated directories and uploaded files do. My testing shows that the last modification timestamp reflects when the files was placed in its current Dropbox location. By interacting with the files via the app there are no timestamp changes. Further testing is needed to see if any changes are reflected from outside the app interaction with the files in the remote storage location.

- Client Modified Date: Time when the file was created. Dropbox will use the file creation time at upload as the Client Modified Date. If the files are in the Camera Uploads folder and follow the naming convention discussed in a previous section, the Client Modified Date is the creation date of the image in real time as long as both values match. This might seem like a distinction with no difference but there is and it is a key one. A creation date for a file is not necessarily the same as when the image was taken in real time. Depending on where the file is in the remote storage location and how it is named one can then determine if the file creation time is the same as when the image was possibly taken in real time.

- Shared Folder ID: One of the folders was shared by me and another shared to me. I find no way to determine directionality by looking at the contents of the database.

I want to emphasize how useful it is to understand the differences in meaning regarding Client Modified Date and Last Modified Date in the previous database. That same understanding will apply to the next database we will analyze. The next database is key because it contains metadata on a large number of images and videos uploaded to the Dropbox account no matter if the files where browsed or accessed by the user via the application on the mobile device.

Metadata/cache.db

As stated previously this database contains information on a large number of multimedia items in the remote storage location. A query was generated (

Images and videos metadata) to show the contents of the /Library/Application Support/Dropbox/

alphanumeric sequence/Files/cache.db database.

The explanations for the Path, Bytes (for file size), Client Modified Date, and Last Modified Date columns are the same as the ones used in the previous database, metadata.db. As seen in the image above some Client Modified Date data might not be moved over. If one accesses the Dropbox storage location via the web interface those dates can be seen.

This means that the modified date in the web interface for the file is the Client Modified Date in the database.

My shorthand, that is not so short, is as follows:

- If file is in the Camera Uploads folder, and it is date timestamp named, and the Client Modified Date is equal to the date timestamp name then the Client Modified date IS the time the picture was taken via a mobile device camera and would reflect the time given by such device. All conditions are necessary for this assumption to be true based on my testing. The underlined word in the last sentence is important because it assumes the mobile device that generated the image or video is keeping time accurately in relation to real time. It is true that science doesn't work in assumptions but it is guided and informed by them. Always do your own tests on your own particular case scenario.

- For all other files the Client Modified Date is the creation date of the file without any assumptions on when the picture or video was taken in real time.

- Last Modified Date is when the files were uploaded to remote storage absent some yet unknown mechanism that affects this timestamp after file upload.

What happens if a file is downloaded from Dropbox to Windows using a browser? Are the Client Modified Date values carried over? If so, where? On Windows systems, and using Chrome as the browser, the following occurs:

- When multiple files are selected for download a zipped files is downloaded to the system containing the selected items. After decompression the files created and accessed times are the same as the Client Modified Date in the database.

- If you download a single file all modified, accessed and created times will be the same and will reflect the moment the file was downloaded from cloud storage locally.

The file properties on the left are from a zipped file whereas the file properties on the right are from a single file download. Both done via Chrome browser on Windows 10.

Here are the values for the same file as recorded in the database.

The difference in hours and minutes is due to setting the time values in the database viewer (Axiom) to UTC-5:00. Notice how time recorded in the database is exactly the same as the created and accessed dates in the unzipped files.

Offline.db

Database records items selected for offline viewing. A query was generated (

Files available offline) to show the contents. The database is located in the /Documents/Users/

UserID/ directory.

Starred_infos_local.db

Database records starred items. A query was generated (

Starred files) to show the contents. The database is located in the /Documents/Users/

UserID/ directory.

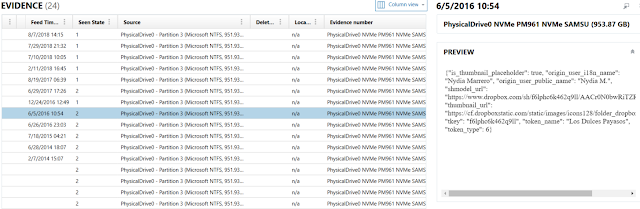

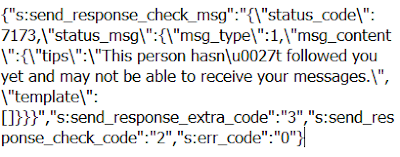

Cache.db / User notifications

Database records user notifications. A query was generated (

User notifications) to show the contents. The database is located in the /Library/Application Support/Dropbox/

Alphanumeric string/notifications directory.

Notice the feed timestamp on the left as well as the content of the notification in JSON format. Since the JSON notifications in the database did not follow a consistent key:value pair pattern they are presented as is. They are small enough for any examiner to read and figure out what they are about.

JSON Files

Dropbox keeps data in JSON files in addition to SQLite databases. The following two files are of great interest. They are located in the /Library/Application Support/Dropbox/

Alphanumeric string/Account/contact_cache directory.

All_searchable

This JSON file contained all the user Gmail contacts for the Dropbox account user. For my sample data I am using my own Dropbox account which is tied to my Gmail. Some of the data kept for the user contacts in the JSON file are:

- Email address

- Interaction info

- Last used time

- Total interactions

- Use type

- Last used time

- Name

- Service types

- Total interactions

- Dropbox profile pic URL if any

Me

This JSON file contained the Dropbox user information. Some of the data kept for the user in the JSON file are:

- Email address

- Name

- Dropbox profile pic URL

- Is_me field with a value of True.

Conclusion

Due to now being able to obtain file system extractions from devices we couldn't in the past it is important we revisit our analysis of what we might think are already well known applications. This is even more relevant when the data we are examining is multi-platform and sometimes we might have to look at it from different vantage points, for example mobile device data in contrast to the same data viewed through a desktop browser.

The eternal caveat still applies. Always test, test and test. And when done, test some more.

As always I can be reached on twitter

@alexisbrignoni and email 4n6[at]abrignoni[dot]com.